The Africa Journals

Chapter 22

Soweto

When the missionaries came to Africa

they had the Bible and we had the land. They

said, “Let us pray.” We closed our

eyes. When we opened them we had the

Bible and they had the land.—attributed to Desmond Tutu

It can be said that it all began in Soweto, though

certainly there were many slums and shanty towns and squatter villages in South

Africa where civil disobedience, and worse, had festered for decades.

To the millions who watched from outside the

country, Soweto is known as “a symbol of apartheid terror and as a symbol of

the heroic struggles of its people against that terror,” wrote Walter Sisulu,

one of the principals of that struggle, along with Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, and

many more.

The reading I had done prior to this journey had

prepared me with a scant overview of Soweto and its history. Briefly, very, very briefly, Soweto and similar ghettos are where the apartheid government effectively exiled the African black,

coloured, and immigrant races to exclude them from the white population in

Johannesburg. The name Soweto is an acronym for South West Township.

During the early and mid 20th century, black Africans flocked into the city to find work

in the gold and diamond mines, but the housing situation was a

catastrophe. The government made

attempts to build simple three or four room

"matchbox” houses, often with dirt floors and no plumbing but a pail, but it could never keep up with demand. Shanty towns sprung up everywhere, frequently demolished by the government with little to no concern about the forcibly-displaced residents.

"matchbox” houses, often with dirt floors and no plumbing but a pail, but it could never keep up with demand. Shanty towns sprung up everywhere, frequently demolished by the government with little to no concern about the forcibly-displaced residents.

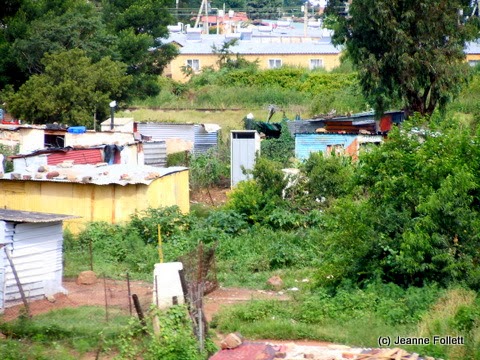

People used whatever material they could find to

erect some kind of shelter, from cardboard and bags to scrap lumber and

corrugated steel. There was no system or

streets or roads.

Today, as our coach passes the beautiful suburbs

of Johannesburg, I watch out the window as the landscape changes to a more

industrial scene.

Brian points out large yellow rows of mine tailings, now being planted with vegetation in an effort to curtail the toxic dust from them.

Brian points out large yellow rows of mine tailings, now being planted with vegetation in an effort to curtail the toxic dust from them.

And then, everything changes. Gone are nice homes and thousands of trees, replaced by tiny brick houses and humble shacks. Even in the yards of the nicer houses, there are shanties and shacks. There are what appear to be new apartment or condo buildings, too. Some of the yards around the small homes are neat and clean, others not so much.

|

| Note the exceptionally tall street light poles, beyond the range of rocks from sling shots. |

|

| Though humble, there is obvious pride of ownership present here. |

|

| Perhaps someday this will be another room on this house. |

|

| The elevation of Soweto is almost 6000 feet, and winter temperatures can drop several degrees below freezing. |

News of the arrival of the luxury coach seems to

spread like wildfire. Everyone looks at

the bus—and waves. Mostly the children,

but if I catch the eye of an adult and wave, it is returned with a smile.

We pass what appears to be an outdoor abattoir with

men butchering animals for sale.

| |

| The umbrella hides the worst of this scene. Live animals were penned nearby. |

A pile of tires alerts us to the next business, where

Brain says the men are selling their “new used tires,” all dressed up with shoe

polish.

Our driver pulls over and a middle-aged man boards. Brian introduces him as life-long Soweto

resident Ngugi, who will be our local guide for the afternoon.

|

| Brian greeting Ngugi |

Rising above the landscape are two huge decommissioned

cooling towers decorated with colorful murals.

The towers, says Ngugi, are where you can bungee or BASE jump between

them, or free fall inside one of the towers.

Ngugi says the acoustics are really good inside the tower and you can

hear yourself scream all the way down.*

And, he continues, there’s a nearby restaurant—in case you lost your lunch while falling.

While today the more than 325-foot towers are a

landmark recreational spot frequented by crazies travelers from around the world, the

towers also represent a part of the shameful history of apartheid. They were indeed cooling towers for the

coal-burning electrical generating plant that supplied power to the whites in Johannesburg,

but not to those who lived in their shadows.

Those people got only the pollution from the coal to go with the stench

of the near-by sewage ponds, also from Joburg.

|

Ngugi continues his non-stop, humorous

patter. I know from our itinerary that

we are scheduled to have lunch in an African restaurant and it is getting to be

that time. We drive up a pleasant

street lined with nice homes and businesses, make a left, and stop immediately.

We get off the bus and Ngugi gathers us up. He waves an arm at the adjacent house.

“This,” he says, “is the home of Desmond

Tutu. This is where he lives when he is

in Johannesburg.”

We are now on Vilakazi Street, the most famous street in South

Africa.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteWe stayed at a Sandals resort in Jamaica. When we ventured outside the resort, we saw poverty similar to that in your photos, Gully.

ReplyDelete